The Curious Case of Dr. Doyle, His Unwanted Creation and the Deceitful Feet of D.D. Hume

/Guest Article By Mark Kennedy, ACSI Canada

“But it can’t be all that difficult to be a ventriloquist, on the radio,” I replied somewhat sarcastically. “I mean you’d have to turn the volume way up to see your lips move.”

In an outdoor restaurant overlooking Port au Prince Bay, the enigmatic Dr. Cooper was absent-mindedly entertaining our Haiti mission team with an artifact from his trunkload of stranger-than-fiction memories. This one was about a stint as a puppeteer on his own radio show. But he wasn’t really paying attention to us, his mind was too busy being enslaved by a game on his new smart phone.

I tried to bring him back to into the real world.

“Could I have a look at that,” I said deftly nabbing the device and depositing it in my shirt pocket. For a few seconds his thumbs twitched where the screen used to be, then, with difficulty, he came out of the virtual trance. His somewhat chastened expression said, ‘Oh right, it’s relationship-building time.’

I continued, “Here’s a mystery for you:

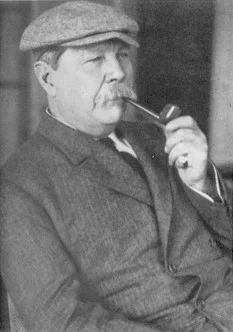

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote the last Sherlock Holmes story almost 90 years ago. Nevertheless in the past few years Holmes has been the focus of two television series, (Elementary and Sherlock), one movie about an elderly Sherlock, (Mr. Holmes), another film where he’s a sort of Victorian James Bond, (Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows) and a Sherlock Holmes stage production (whose name I forget) at one of Toronto’s most prestigious theatres. Last December there was even a PBS mini-series about Holmes’ creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, (Arthur and George). So here’s the question:

‘What is there about the Sherlock Holmes character that is so appealing for modern audiences?’”

The distracting question worked. Dr. Cooper was intrigued and so were our team members. I could see his cerebral gears beginning to grind into action. Then suddenly they stopped.

“Wait a minute, I hope this doesn’t mean you’re going to do one of your world author articles about Conan Doyle, a run of the mill peddler of Victorian detective stories.”

“Who me?” I said in feigned shock and then I smiled. “Don’t worry, I get your concern about detective stories writers. Maybe I should do an article about a brilliant, highly accomplished, internationally famous author –someone like that medical doctor who produced 21 novels, 150 short stories, several historical volumes, at least a dozen popular stage plays and multiple magazine articles – an amazingly colourful person who introduced cross country skiing to Switzerland and whose other interest ranged from cutting edge medical research to Paleontology to warfare strategies, public justice and amateur athletics.

“Now that’s more like it!” He replied.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was born in Edinburgh in 1859 to semi-impoverished Irish Catholic parents. His father was an artist with an ethereal temperament, who eventually succumbed to alcoholism and mental illness. His mother, whom Arthur called “The Ma’am”, was the family rock, raising their 9 children and paying the bills. From Arthur’s earliest days in Jesuit schools he showed a gregarious personality, an eager interest in all kinds of learning, outstanding athletic skills and remarkable storytelling ability. But he also struggled with a spiritual conflict between the beliefs of his favorite author, the anti papal Lord Macaulay and the school’s Jesuit teachings. It came to ahead when a Catholic priest proclaimed in a school Mass that only Catholics go to Heaven. That left Macaulay and others out so Arthur decided to abandon Catholicism and Christianity along with it. (Although The Ma’am’ couldn’t buy the priest’s assertion either, she reacted by becoming an Anglican.) So Arthur entered adulthood as an aspiring secular materialist – someone who believes the only realities that matter can either be experienced by the 5 senses or understood by the human mind. That meshed with ‘progressive’ thinkers of his day who rejected the evangelical Christian perspective that was pervasive in late 18th and early 19th Century Britain.

“I had laid aside the old charts” (of Christianity) “and had quite despaired of ever finding a new one which would enable me to steer an intelligible course, save towards that mist which all of my pilots, Huxley, Mills, Spenser and others could see ahead of us.” (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Memories and Adventures, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009).

But Arthur was never comfortable with secular materialism. It warred with some of his strongest convictions.

For one thing, it denied or at least denigrated human love, and love was a reality he knew well both in his family life and in his romantic encounters.

It also conflicted with Doyle’s powerful commitment to biblical morality, a belief he held despite his rejection of foundational Christian doctrines. The focus upon Christian behaviour apart from faith was pretty common from his day up until the latter part of the 20th century. After that people seemed to realize that, without the source of Christian virtue, there was no point keeping the behaviour. Throughout his life Doyle clung to the misguided concept of ‘Jesus, the great moral teacher.’ If only he had read C.S. Lewis:

“A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

Finally, secular materialism was at odds with his conviction that his life followed an intentional design. He spoke of an impersonal guiding force called ‘providence’, but he must have realized that where there’s a design, there must be a Designer.

His career as a doctor wasn’t very successful. To supplement a meager medical income Doyle began writing short stories for various magazines along with some historical novels and plays. Those novels were always his favorites. He loved them because, to his mind at least, they were real literature unlike his wildly popular Sherlock Holmes stories. The historical novels and plays were popular in their day and, to Doyle at least, they were art, but Holmes paid the bills.

I’ve canvassed friends about the remarkable modern appetite for Sherlock Holmes. At first they’re quietly pensive. They know the Holmes adventures aren’t just standard detective tales, but it takes a while to figure out their distinction.

Sooner or later people realize that Holmes’ personality makes the difference.

As a fictional character, he has some very unappealing peculiarities - no friends except Watson, no family except his brother Mycroft (who’s even more coldly intellectual and reclusive than Sherlock), and no romantic interests. The closest Holmes comes to love is a deep admiration for “The Woman”, Irene Adler, because she once outwitted him. And there is absolutely no evidence that he has any spiritual awareness. He’s not openly atheistic, just uninterested – much like the young Doyle.

But other aspects of Holmes’ character have always managed to fascinate readers.

First and perhaps foremost, he’s a brilliant magician who doesn’t hide the mechanics of his illusions. He astounds readers with seemingly omniscient feats of deduction and makes us wonder “How does he do it?” But unlike a stage magician, Holmes tells us the secrets of his art.

When meeting a new client, Mr. Jabez Wilson, in The Red Headed League, he observes, “Beyond the obvious fact that he has at some time done manual labour, that he takes snuff, that he is a Freemason, that he has been to China, and that he has done a considerable amount of writing lately, I can deduce nothing else.”

Then he proceeds to tell Watson and Mr. Wilson the logical steps that led him to those conclusions.

Second , he’s a knight errant, solving obscure intellectual conundra purely in pursuit of justice and virtue. Financial gain and public acclaim don’t matter to him. He is a consulting detective, not an investigator for hire and he’s embarrassed by the notoriety that Dr. Watson’s published accounts brings. In The Sign of Four, Holmes comments on Watson's first story about their adventures: "Honestly, I cannot congratulate you upon it. Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism...”

Third, Holmes is a tutor who shows us how to observe rather than just see, He instructs readers in the skill of distinguishing reality from mere perceptions of reality, to see “with, not through, the eye”, as William Blake’s puts it.

In A Scandal in Bohemia Holmes tells Watson, “You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear. For example, you have frequently seen the steps which lead up from the hall to this room.”

“Frequently.”

“How often?”

“Well, some hundreds of times.”

“Then how many are there?”

Holmes would reject with scorn the fatuous 21st Century advertising mantra, “Perception is reality”. He knew the difference between the two.

Every world authors reveals his beliefs and values in his writings –his worldview- whether he intends to or not. And it’s important for Christian school students to discern and evaluate those worldviews in light of the principles in Scripture. The Holmes stories are suffused with Doyle’s early materialistic perspective. Holmes is the quintessential secular materialist – a man who solves all mysteries and brings the triumph of justice through careful observations, scientific knowledge and human reason.

But as Hamlet says, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” And Holmes’ creator began to see what he meant. Doyle was developing an awareness of spiritual, or at least supernatural aspects of life - but sadly, that didn’t involve Christianity.

“If I live after death… Only one thing would amaze me. That would be to find out that Orthodox Christianity is literally true.” (Arthur Conan Doyle 1911 as quoted in The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) and as Doyle grew increasingly dissatisfied with both materialism and its literary personification in Holmes, he decided to murder the great detective. After the publication of The Final Problem where Holmes and his nemesis, Professor Moriarty, plunge to their deaths at Reichenbach Falls , his reading public were devastated. So was “The Ma’am”. Fans worldwide demanded an immediate resurrection. So, reluctantly, using a fair amount of intellectual gymnastics, he brought Holmes back to life in The Adventure of the Empty House . From then on however, the Sherlock stories never quite had the same quality.

But none of that really explains Holmes astonishing appeal to 21st Century audiences, how, in some way, the ‘deep’ of modern people calls to the ‘deep’ of the world’s only consulting detective. It seems to me that the link is a shared secular materialistic perspective on life. In a society where church attendance drops with every new year, especially among the young and where there are twice as many Canadians with no faith as there are evangelicals (in the States the numbers in both groups are about equal) there’s a special attraction for a secular character who is completely logical, scientific, inerrant and self sufficient- someone who discovers truth and brings justice by himself using observable facts and human wisdom, without any need for any higher power.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not attacking Holmes. I truly enjoy the Holmes mysteries. They’re wonderfully entertaining escapist literature that let us retreat into a comforting fantasy: the idea that all crime can be solved by a brilliant detective outsmarting wrongdoers. It’s a simple formula and it’s simply false, or at least misleading. When it comes to the bigger and more foundational concerns about crime, things like the challenge of reducing criminal behaviour and reforming criminals, Holmes is out of his depth. And today’s alarming rates of criminal incarceration and recidivism in North America show that even the brightest secular materialistic thinkers aren’t making much of an impact either. That’s because crime isn’t just the product of destructive social and environmental factors. Crime starts with human hearts, and when hearts are changed, outward behaviours start to change too. Secular materialistic philosophies can’t produce that change. Christ can. That explains why groups like Prison Fellowship have been so remarkably successful in reforming criminals while the criminal justice system hasn’t. Prison Fellowship presents Christ’s offer of forgiveness and transformation appealing to the heart first, then to the mind. One of history’s most brilliant thinkers, 17th century philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal recognized the significance of that priority, “The heart has its reasons which are unknown to reason…. It is the heart which is aware of God, not reason: that is what faith is: God perceived intuitively by the heart, not by reason.”( Les Pensées)

“So that’s your answer to the riddle, is it?” Summarized Dr. Cooper, now fully engaged in the discussion. “Basically Sherlock Holmes is popular because he’s a 21st Century North American dressed up in Victorian clothes?”

“Sort of.”

“And if criminals’ heart attitudes would change there’d be a big reduction in crime?”

“That part’s right.”

“What happened to Conan Doyle?”

“The great man came to a pretty sad end. In his old age, Doyle couldn’t distinguish perception from reality. If there was a book about those final years it might be called A Study in Charlatans because the author became an enthusiastic promoter of Spiritism- a pseudo religion whose advocates claimed, among their many loony activities, to communicate with the dead. Incredibly, the man who created literature’s most acutely rational and discerning detective was taken in by a plethora of scoundrels and con artists ranging from 2 young girls whose ‘photo-shopped’ picture seemed to show pixies dancing in their garden, to Scottish ‘medium’ D.D. Hume and other fraudsters of his ilk. They all had skills that deceived the gullible. Hume is an especially interesting study, maybe the archetype of all spiritual mountebanks and, to Doyle at least, the equivalent of a Spiritist saint. Hume gained notoriety thanks to his brilliantly deceitful feet. With them he bamboozled prominent and famous people, including scientists and members of European royalty, by producing noises and even phosphorescent ‘apparitions’ during his séances. He was finally caught out by a séance participant who pretended to take a washroom break but secretly watched Hume’s pedal manipulations from behind.

If Doyle hadn’t abandoned Christianity he might have seen through the fraudsters and stayed away from spiritism, maybe by heeding the warning in Leviticus 19:31, "Do not turn to mediums or seek out spiritists, for you will be defiled by them." Or at least he could have learned from King Saul’s disastrous encounter with the Witch of Endor in 1 Samuel 28.

Harry Houdini tried to warn him.

Doyle was convinced that Houdini, history’s most famous illusionist and escape artist, was a spiritual medium. Houdini denied it. In fact Houdini committed a significant part of his latter career to debunking mediums and other spiritual fraud artists. He was even part of a Scientific American committee that offered a cash prize to any medium who could successfully demonstrate genuine supernatural abilities – no one could. .And he was a devastatingly successful debunker because, as a skilled magician, he recognized the mechanics of successful deception. Once Houdini performed an illusion specifically to help free Doyle from the influence of spiritists. He made a cork ball covered with ink appear to write “Mene, mene, tekel upharsin,” without any apparent human assistance. Houdini explained to Doyle that he used simple equipment and scientific principles to do it. His explanation failed. In Doyle’s eyes, Houdini was a medium, the worst kind of medium because he denied the “gift” with which he had been empowered. Their friendship ended.

“Is that all about Conan Doyle for now?” asked Dr. Cooper with some impatience, so I knew he was eager to lead us on another dawdled down Cooper Memory Lane.

“When I was a pastor I once rented a tent at the psychic fair in our town.” He said.

A stunned silence fell upon the mission team but not on me.

I stifled a yawn and drawled, “Really? You amaze me, Holmes.” I’d heard this one before.

“Yes,” he continued, “Then, outside the tent, I put up a sign that said, “Come in and Have your Psalm Read!”“Note, it said ‘Your Psalm’, not ‘Your Palm’”. I clarified for the benefit of those trying to move beyond the shock of the psychic fair concept. “And don’t forget to tell them about the goat.” Jaws dropped.

“Oh right, I borrowed a friend’s goat and tethered it outside the tent.”

“The reason being…………..?” I prompted.

“It seemed like a good idea at the time.”

“Ah.”

“When people came into the tent, I’d ask them their birthday, and then I read them the corresponding Psalm from the Bible. So if their birthday was May 19th I’d read Psalm 19.”

“And did this produce a great spiritual harvest?” I asked (sarcastic again, I know, but sometimes I can’t help myself).

“Well, the jury’s still out on that one.”

“What did people in your congregation think?” asked one of the less aghast team members.

‘ I’ll bet the jury wasn’t out on that one,’ Went through my mind but my lips were sealed.

“Some thought it was a bit unusual, maybe even a little eccentric.” He had to admit. Meaningful glances spread among us.

“Sometimes perceptions might just be reality after all,” I said but he wasn’t paying attention. The good Doctor had managed to liberate his phone from my shirt pocket and, with thumbs merrily twitching, he’d once again escaped into that virtual land somewhere over the rainbow, or at least on the other side of his smart phone screen, where a flock of Angry Birds demanded his immediate and undivided attention.

______

Epilogue: I’ve just seen an ad for yet another Holmes related television series entitled Houdini and Doyle. The fascination continues.